[AR] TANWEEN: (NUNATED) SHORT VOWELS

WHAT IS TANWEEN

Whether from loneliness, narcissism or shoe-envy, sometimes our short vowel buddies duplicate themselves. Thus becoming tanween.

Just as one sandal can become double sandal, all the short vowels can double themselves:

damma > double damma

fatHa > double fatHa

kasra > double kasra

BEHAVIOUR

Both tanween and regular short vowels guide pronunciation and indicate case.

In addition to this, tanween also have indefinite super powers. If you find tanween on the end of a word you can (almost) guarantee the word is indefinite. Head here for more on definiteness.

PRONUNCIATION AND NUNATION

Short vowels tell us whether to say 'oo', 'ah' or 'ee' in the absence of long vowels.

As soon as the short vowels become doubled, they get pronounced as though there is a tiny invisible n (ن) on the end. Where you say 'oo' for damma, you say 'oon' for double damma. 'Ah' becomes 'an' and 'ee' becomes 'een'. For this reason, tanween can also be described as nunated short vowels.

CASE

Case is a beast. We will look at it briefly, but you can find more details about it here.

Each of the short vowels have a particular kinship with a case. Of course there are exceptions, but we'll look at the basic rules for now.

Damma: nominative case

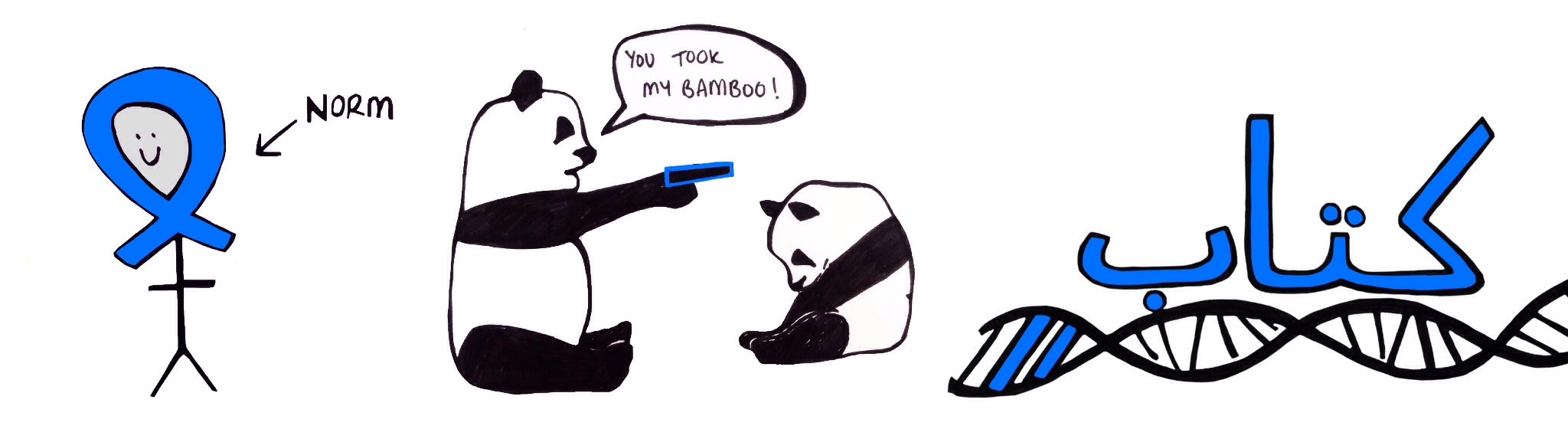

Meet Norm [image below]. Norm is a damma with a body attached. Any time you see a damma in a sentence just think about Norm going about his day in the NORMinative case. Nominative case.

FatHa: accusative case

Move over normal Norm. Panda is going to help us out with accusative. Instead of taking responsibility for missing bamboo, panda perpetually accuses other pandas of stealing it. Panda's extended accusing finger looks a lot like a fatHa. The same applies to anyone's extended accusing finger. Accusative case.

Kasra: genitive case

This is a bit of a stretch, but imagine sentences are built on strands of DNA instead of lined paper. Because why not. Now we're going to focus on a section of DNA: genes. Every time there is a short vowel that sits below the baseline, on the double helix, pretend it's part of a gene. Naturally, short vowels under the text (kasras) are in the GENE-itive case. Genitive case.

WRITING TANWEEN AND ALIF SEATS

This is the part where things get exciting. The part that will explain why some tanween are lounging on a lawn chair in the banner image. When we start nunating our short vowels, some can sit themselves on the end of a word no problem. Others need to have an alif to climb on.

If you find yourself nunating a damma or a kasra, you can ignore the alif seat and go about your business placing tanween on the end of words.

If you're wanting to nunate a fatHa, step on up and reacquaint yourself with alif (ا).

Remember that fatHa is the short-vowel version of long-vowel alif, so it kind of makes sense that they'd be buddies on the end of words.

Double damma and double kasra don't need an alif seat.

Double fatHa does need an alif seat, most of the time.

DOUBLE FATHA

For everyone's sanity, let's say an alif seat is the default for double fatHa. Then there are exceptions: when double fatHa doesn't need a seat.

NO ALIF SEAT

Words that end in ta marbuta (ة) or alif maksura (ى).

Words that end in hamza (ء), if hamza is preceded by alif. Because one alif beside hamza is enough *.

ALIF SEAT

Words that end in hamza (ء), if hamza isn't preceded by alif.

Everything else.

* What's this business about hamza being preceded or not precede by alif? Hamza and alif have a complicated relationship. In the context of double fatHa, it's a love-hate kind of thing. Hamza needs alif. But like all things in life, moderation is important. So having an alif before hamza makes them both very comfortable. Just as adding an alif after hamza is appreciated. But having alif both before AND after hamza is just ridiculous. Don't do it.

MORE ON HAMZA

If we decide hamza needs to be followed by an alif, we have one more decision to make: does the hamza need a little seat as well?

If the character before hamza is a one way connector, hamza remains independent and sits cross-legged on the ground.

e.g. جُزءاً

If the character before hamza is a connector, hamza extends an olive branch and joins it by sitting on a ya (ي).

e.g. شَيئاً

Now, for the flowchart-inclined:

WHEN TANWEEN IS INVISIBLE

Like most things we learn in Modern Standard Arabic, case endings and tanween won't be written in a lot of text material. However, even when tanween isn't included, the alif seat under double fatHa still finds its way onto the end of words that need it. The alif seat must be included, even if the double fatHa isn't. Kind of like railway tracks that remain in the ground long after the train has stopped running. Evidence of something that was.

Example