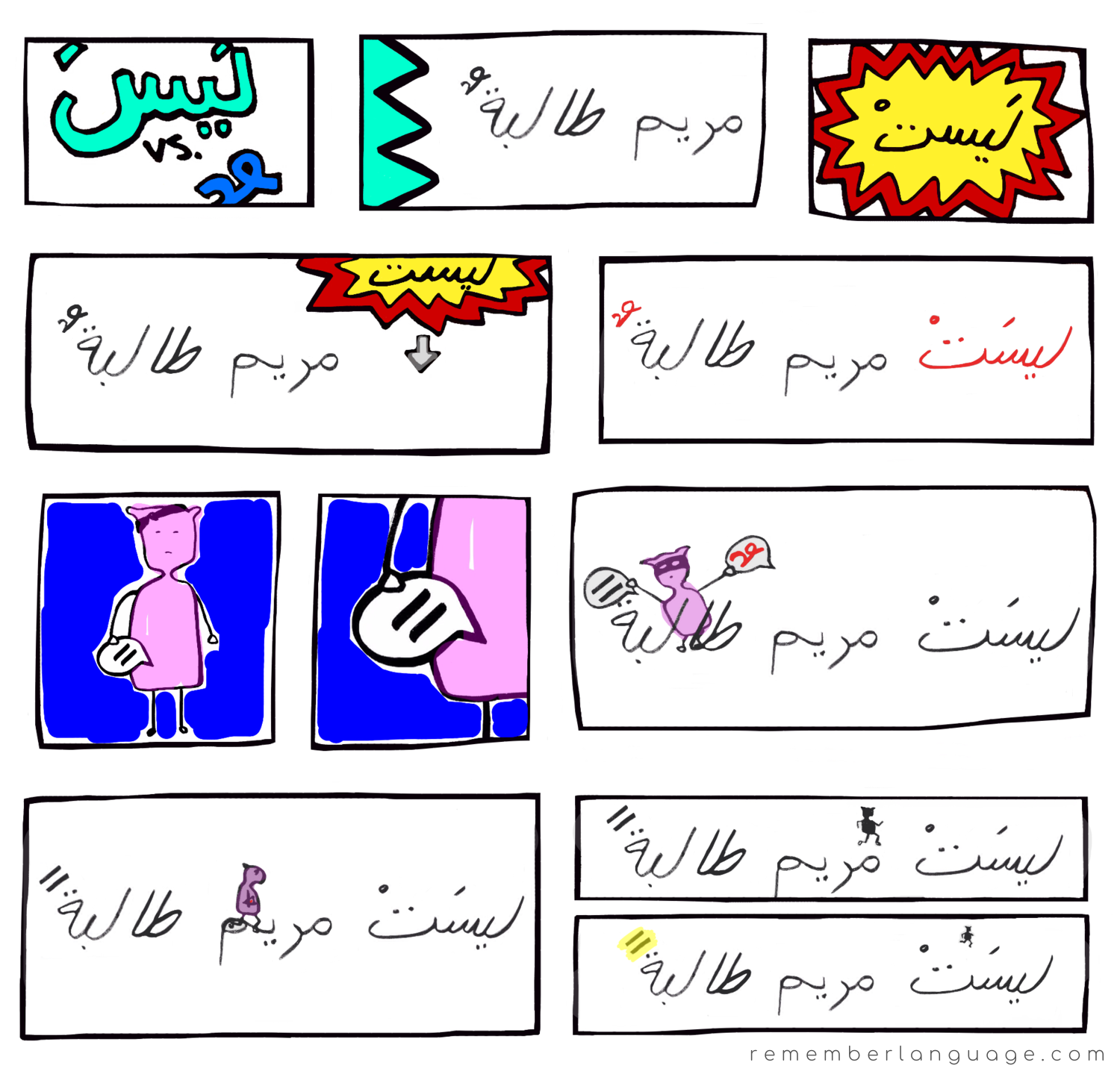

[AR] LAYSA (ليسَ): NEGATING PARTICLE FOR NOUNS & ADJECTIVES

INTRO

Fig. 1

Laysa is a verb refuser: he simply hates verbs. If there’s a verb in a sentence, he won’t be anywhere in sight. Always with the nominal sentences, is Laysa.

Laysa is quite the bessimist*. Glass half empty kinda guy. Laysa’s role in life is to negate sentences.

Laysa can park himself in the middle of sentences, or right up the front at the beginning of a sentence. Heck, Laysa can beget a sentence, if he so desires.

GENDER

Laysa has a lady friend who might be worth mentioning. Before you ask how such a moaning particle got a woman, I’ll let you know she’s as negative as he is.

Laysat is more or less the same as Laysa but with different reproductive organs. They’re that couple you know who are so similar sometimes you think they’re the same person.

They are the kind of lovers that you never see together (figure 1 is actually photoshopped; it was previously a photo of Laysa holding a cup of tea). Only one of them will occupy the place in your sentence. Before the grammarians sat and lay down some rules, Laysa and Laysat would fight over who could go damage a sentence. To provide some order, it was decided they would each only communicate with words of their own gender. Discriminatory? Perhaps, but that’s for another conversation.

If the noun or adjective that needs negating is a handsome man word, Laysa (ليسَ) will take the job.

If the noun or adjective is a lovely lady word, Laysat (ليسَت) will come through with the goods.

Fig. 2

CASE

Now seems a good time to mention any clubs, cults or gatherings that Laysa partakes in. Most recently, Laysa has been involved in the Olympic Stamp Collecting Championships, as well as the more commonly accepted lifetime membership with The Sisterhood of Kaana. This may be confusing as Laysa is a boy, but it's a very welcoming sisterhood. Kind of.

Like a bunch of other Arabic words, Laysa has a tight kinship with a selection of gown-wearing particles. Each Sisterhood is defined by their case-ending preferences.

In accordance with the Sisterhood of Kaana, Laysa and Laysat don’t just roll in unnoticed. Unlike Lakinna, who comes in and makes the subject get nervous and change case, Laysa and Laysat both make the predicate get twitchy and take on a different case.

See figure 2 for a little reminder of who's the subject and who's the predicate. We have Myriam suited up in the role of subject, and 'student' as the additional information, aka. predicate. Everyone here is currently in the nominative case, as confirmed by the little squiggles on the predicate's left ear. Once Laysat rolls on in, our predicate friend will be deemed accusative. Laysat trumps squiggles.

Fig. 3

And if you feel like watching a ridiculous video version I made (0:39):

Fig. 4

Laysa and Laysat actually just like to collect dammas and double dammas; you should see their display cabinet at home. See figure 4. Laysa and Laysat pocket the damma and double damma of the predicate and replace it with a fatHa (making the predicate accusative).

FatHas basically look like recycled apostrophes that have been lying around from incorrect and neglectful use in English. Laysa and Laysat’s criminal activity could well be inhibiting people from processing things in English.

PRONOUNS: FIRST, SECOND, AND THIRD PERSON

THIRD PERSON

So far, everything I’ve said has been relevant when talking in the third person. About one person.

Myriam is a student. Myriam isn’t a student. Myriam is an envelope. Nigel isn’t a gummy bear. Et cetera.

SECOND PERSON

If you’re the kind of human who doesn’t like talking directly to people, you don’t need to know how to use Laysa in the second person. You may never imagine a situation where you tell Nigel directly, ‘you’re not a gummy bear, Nigel. Stop banging on about your squishy yellow outfit. No one even likes the yellow ones’.

However, if you’re anything like me, you may like to have conversations with people in your head. And there’s nothing more satisfying than being grammatically correct when formulating the perfect comeback, 3 hours post-quip.

As much as Laysa would claim to froth over an opportunity to kick Nigel in the shins, Laysa is all words and no action when it comes to direct conversations.

As mentioned, Laysa and Laysat only talk about people (third person). While Laysa and Laysat do an excellent job of being super negative and slightly back-stabby, we need some particles that are a bit more aggressive and confrontational for direct conversations.

Welcome: Lasta (لستَ) and Lasti (لستِ).

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

At last-a, we have some robust negators. These two loot case endings and divvy their workload in the same fashion as Laysa and Laysat (by gender), but with more gristle. Before you’ve even thought to confront Nigel about his gummy bear obsession, Lasta is there, knocking at Nigel’s door.

FIRST PERSON

Jump, for a moment, into Nigel's shoes. As Nigel has the news broken to him, he needs to find the vocabulary to process the information. Nigel needs to be able to say, 'I am not a gummy bear'. No one will be surprised at this point to discover there's another form of laysa, completely suited to talking about the self. Because Nigel is only one person, we'll stick with the singular version of self: I.

Fig. 8

Introducing: Lastu (لستُ).

Lastu is both male and female. Confusing? Don't be so narrow minded. Lastu is the most self centred of the particles (see figure 8). Lastu cannot fathom a sentence where s/he refers to anyone other than her/himself. Lastu thrives in places of severe isolation, and minds of narcissists. When everyone else is conversing about you, they, him, or her, lastu is just saying I, I, I, me, me, me. 'I am not your father'. 'I am not this'. 'I am not that'.

Just think, if all the negating particles perished and the last two needed to repopulate the earth ... compare the 'last two' with 'Lastu'. Either combination/scenario would be as effective at prolonging life, because Lastu would gladly reproduce with itself. I'll leave that image with you.

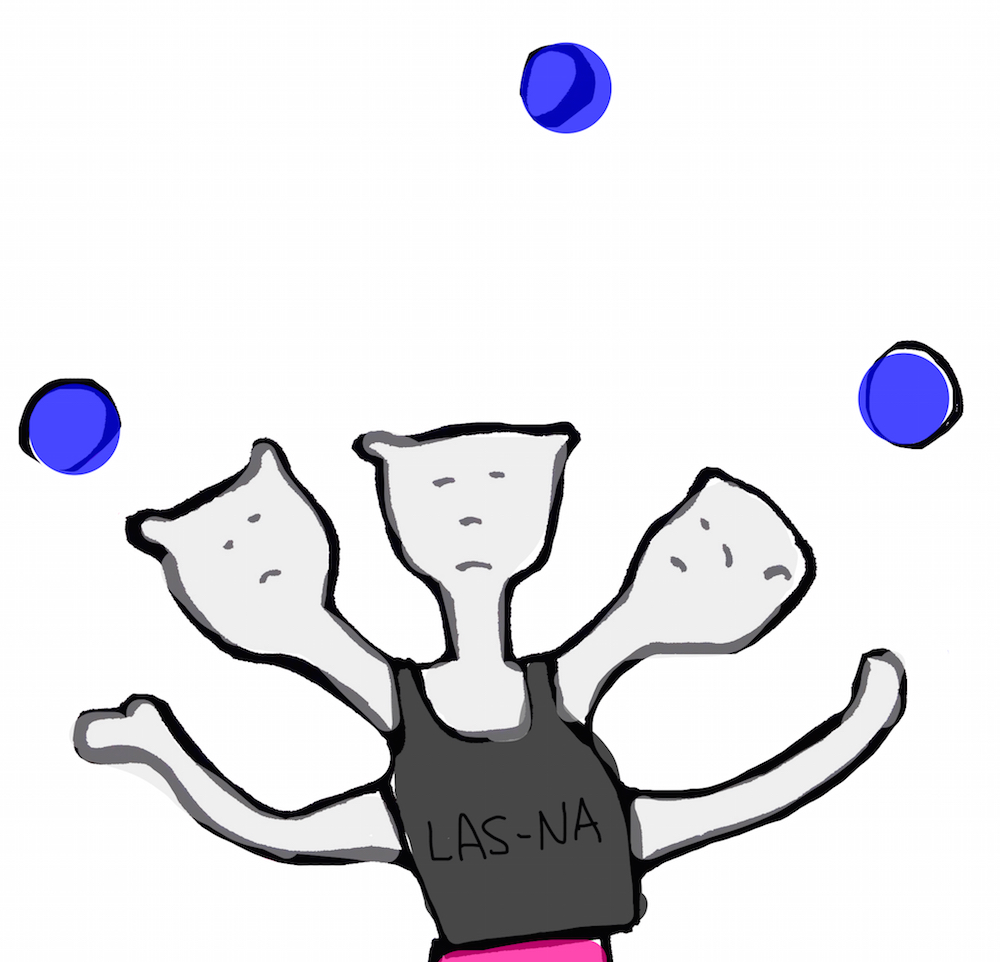

Now to thrust us all into hypothetical-land for a moment. Suppose Nigel was more than one person. Suppose Nigel was, in fact, a group of three people. Or two. Or seven. Or nine. Of any male to female ratio. Naturally, the 'I' needs to become 'we'.

Fig. 9

Nearly as self-absorbed, but slightly less lonely, is Lasna (لسنا).

The noun and adjective negator for the plural-self (see figure 9). 'We are not your father'. 'We are not these things'. 'Or those things'.

This particle also has no regard for gender. You can be one male with two females, all females, all males. Whatever.

Everyone involved in the 'we' does a collective resounding 'nah'. A Las-nah. 'We are not a bunch of bananas'. Bana-nah. Las-nah bana-nah.

NUMBER

As well as being picky about gender, case, and pronounery, Laysa (and his variations) are quite pedantic when it comes to number agreement (dual or plural).

I’d recommend not having more than one friend, because then you don’t have to learn dual or plural. However, if you talk to or about more than one person there’s a whole new set of Laysa forms available. They’re kind of the Rolls-Royce of the negating particles. They’re the Shakespeare to your texting abbreviations. They’re the semicolon to your full stop and start a new sentence. The oh-you-know-how-to-grammar of the conversation.

To be honest, you’re not going to need these negations in regular conversation. We will look at the dual and plural particles for good practice, but for the sake of everyone’s sanity, we’ll talk about them in a separate post.

Until that post happens (I may procrastinate from that until the end of time), there’s good news. There is a trick. A beautiful trick. Etch this into your brain. Write it on the back of the bathroom door. If you put Laysa before the noun (or pronoun) or adjective, you don’t need to use the fancy particles.

If Laysa is before the noun (or pronoun) or adjective, it only needs to agree in gender.

If Laysa is after the noun (or pronoun) or adjective, it has to agree in gender and number.

Choose wisely. Unless you don't mind getting your number agreement jig on.